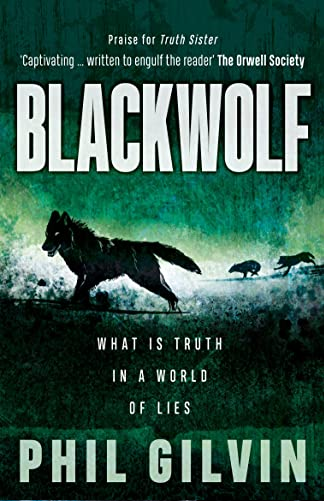

Back in 2018 I reviewed Phil Gilvin’s debut dystopian novel Truth Sister, an exciting exploration of power, gender roles and oppression. It’s set in the Women’s Republic of Anglia in 2149, where women are in control and men have no power. We’re now fast-approaching the release date of the other half to this duology, Blackwolf, which will be available on 21st April 2022.

In Blackwolf, alongside devastation caused by climate change and dwindling energy, a plague has swept Britain, killing large numbers of women and almost all men. As the Women’s Republic of Anglia struggles to continue cloning, ex Truth Sister Clara Perdue is helping her mother escape prison. But is this even possible against the Republic’s prohibition on Naturals? Meanwhile, Jack Pike has fallen in with a warlike chieftain in the disputed territory between Anglia and Wessex. Drawn into a fight that’s impossible to win, will he and his friends survive? And when Clara and Jack’s paths cross again, can they put the past behind them and trust each other once more?

This novel feels immensely important and very close to home right now, and I’m thrilled that Gilvin has shared an extract with Dystopic, which you can read below. If you’d like to get a copy, Blackwolf is being published through Aelurus Publishing and is now available for pre-order – you can find buying links on his website.

–

Author note: Blackwolf starts with Clara Perdue escaping with her mother, Sophia, from prison on the Isle of Wight, as another plague strikes down the prison guards. Now they have enlisted the help of a man called Khan, who harvests plastic waste from the sea and sells it for recycling, to row them across the Solent.

‘Always the questions!’ said Khan, and he jerked his head behind. ‘See the lights? Over there is Lymington, and there’s Milford. And can you see the lighthouse?’

‘Just about.’

‘That’s where we’re going. Now shut up. We need to row.’

Clara pulled, and pulled, and pulled, but now their progress slowed. The air was full of spray, the cold wind slapped her face and hands, and the darkness enveloped them completely. In front of her was Khan’s back, his shoulders rippling with each pull. When the boat’s pitching and rolling allowed her to glance to the right, the dim shoreline was still there. Her hands were beginning to hurt and she was about to ask Khan if he had any cloth, or even gloves to wrap them in, when a cold wave splashed completely over the boat, soaking them all before pooling around their feet.

Khan swore. ‘Told you. That wind’s getting up,’ he shouted to Sophia. ‘Steer more to your left. A bit more!’

‘What’s wrong?’ Clara shouted.

‘Nothing,’ said Kahn. ‘Just keep going!’

On and on they went, Clara’s arms aching and her feet turning numb. Twice more, waves toppled into the boat, soaking them afresh and filling the bilge still further.

Khan glanced over his shoulder. ‘Keep pulling! The tide is turning!’

‘There’s the lighthouse,’ cried Sophia.

Then, as the boat dropped down the side of an especially large wave, there came a loud thud from the keel. Clara cried out.

‘It’s okay,’ panted Khan, ‘don’t worry – she’ll hold.’

‘No,’ cried Clara, ‘we’re going to sink. We’re full of water!’

‘It’s the sunken fort,’ said Khan. ‘We’re going over the top of it. Row!’

They pulled again. One stroke, two, three, then, suddenly, calm. They were still out on the dark waters, but the waves had subsided into a gentle swell and the hiss and the splash and the rumble had faded.

Khan held up a hand. ‘Okay,’ he panted. ‘Rest a minute.’

Clara peeled her sore hands from the oars and tried to warm them under her armpits. To her left rose the white pinnacle they’d seen earlier, just visible as a pale spike in the black night. It climbed some sixty feet above the waters, its pinnacle fading into the blackness and the stars.

‘What’s happened?’ said Sophia, looking around at the calmer waters.

‘We’re inside the lagoon,’ panted Khan. ‘The old fort makes a reef. See there, to seaward, where the waves are breaking? We did well.’ He nodded. ‘And – yes – the plastic’s all safe. He is good, is Reynard.’

Clara looked up. ‘Who?’

‘The boat,’ said Khan, patting the gunwale. ‘I gave it a man’s name. Reynard, foxy, good and solid. Here, pass me that lamp.’

He produced a box of matches from a breast-pocket and, carefully lighting the lamp, he edged past Clara and fixed it to the prow.

‘W-what happens now?’ said Sophia. Her teeth were chattering.

Khan swept an arm round to his right. ‘Under there is the causeway that used to lead to the old fort. That’s like another breakwater. But we’ve still got another mile to row.’

‘A mile?’ cried Clara. ‘I’ll never make it!’

‘It’ll be easy now,’ said Khan, ‘so stop whining. See the lights?’ He pointed over Clara’s shoulder.

Clara turned. Low over the water she saw three yellow dots like low stars, their reflections rising and falling in the waves. ‘That’s where we’re going?’ she said.

‘Let’s row,’ said Khan. ‘Ms Sophia, steer for the lights.’

Clara closed her eyes and pulled once more. Her back ached, her thighs ached; she felt her head lolling forward. But Khan was right, the going was easier now. The oars spent more time actually in the waves instead of thrashing the air between, and she didn’t have to lift them so high.

‘Beneath us,’ said Khan, ‘there is a drowned marsh. Further on there’ll be submerged houses, so we will have to go carefully. Though most of those have got washed away by now.’

‘Argh!’ exclaimed Clara. ‘Something caught my oar!’

‘Keep rowing,’ said Khan.

‘That’s another!’ said Clara. ‘On the other side. There’s something in the water. Is it logs?’

‘Is it plastic?’ asked Sophia. ‘Like you collect?’

Now the keel was thumping against obstacles, bump, bump, bump, under the boat.

Khan stopped rowing. ‘Give me the lantern,’ he said to Clara. Then, grabbing it, he held it over the side. Clara screamed and toppled back onto the still-watery boards.

A face looked up at her from the water, a bloated face with staring eyes and exposed teeth. The man lay on his back, his arms floating wide as he bobbed up and down and bumped repeatedly against the boat. He was black-skinned and wore a thin, torn shirt that billowed up then sucked back against his body. As Clara whimpered, Khan swept the lantern to the opposite gunwale. Another body, this one face-down, and another, and another. Sophia gave a wail and covered her face.

‘D-dead people,’ stammered Clara. ‘What are they doing here?’

Khan stood and, turning up the wick, held the lantern higher. Clara could see there were more bodies, bobbing on the dark waters like jettisoned cargo, like a mat of kelp, an army of sea-dead coming to suck their boat down and down . . .

‘Let’s get out of here!’ she cried. ‘Please!’

Khan, too, was shaken. Unsteadily, he grabbed one of his oars and scrambled past the plastic bale. ‘Poor people,’ he said, staring at the shapes as they rose and fell on the surface. He shook himself. ‘I will get into the prow and push them out of the way. You row when I tell you.’

It was a terrible few minutes. Khan pushed and splashed with his oar and Clara rowed when he’d nudged each body out of the way, but she felt at every stroke that dead hands were snatching at the blades, that dead eyes were staring at her, willing her to join them in the dark water. Time and again as she drew the blades clear of the water, she felt a resistance, a scraping, a heaviness. She felt like she could row no more, like she wanted to curl up and make the dead go away. But, at last, the waters cleared and their progress was smoother. Khan returned to his seat and they rowed in silence.

After another twenty minutes, when Clara felt her arms and legs cramping, Khan held up the lantern again. ‘We’re here,’ he said. ‘I can see walls in the water. Go slow.’

‘Who were they?’ said Clara. ‘Who were those bodies?’

‘Oh,’ said Khan. ‘They could be Africans. Sometimes they make it this far.’

‘Africans! How did they get here?’

Khan shrugged. ‘You know it. In Africa the people are starving. These people, maybe they were on a boat that was too crowded.’

They came all the way to Britain?’ said Sophia.

‘Pah! I bet they tried Spain and France first,’ said Khan. ‘Nobody wants them. But the Channel was too much for them – and then the sea has washed them here. The sea, she always wins.’

The boat began to foul on dark things in the shallows, but they weren’t bodies this time. Here a tree-stump showed clear of the surface, there the remains of a brick wall. There was no room for Khan and Clara to push their oars in deep anymore, and their progress slowed.

‘We can’t get out yet,’ said Khan. ‘There’s mud here.’

Eventually the lantern-light showed grasses thrusting up from the water, then bunching tighter into thick tufts; then they saw, rising ahead of them in a gentle slope, boggy ground. Khan made them climb out, plunging thigh-deep into the cold water before pushing the boat up the slope, over the tussocky grass and clear of the shallows. He tied the boat to a leafless hawthorn hedge that stretched across the grass in front of them, then looked up at the sky and sniffed the air.

‘You are lucky,’ he said. ‘We can leave the plastic here. It will be safe till morning.’

‘Lucky?’ said Clara.

‘Otherwise you’d be helping me roll it to Milford,’ he said with a chuckle. ‘Now,’ he added, pulling something from his shirt pocket. ‘Payment, lady.’

Clara gasped. Pointing at Sophia was a small pistol, its muzzle gleaming in the lantern-light.

‘No!’ Clara cried. ‘You can’t – I thought you were helping us! We haven’t–’

Gently, Sophia pushed her aside. ‘Clara, Clara,’ she said, ‘it’s all right. Here,’ she added to Khan. ‘As I promised.’ And she held up something long and sinuous that glittered and sparkled, reflecting back the lantern-light below and the starlight above, twinkling as it swung to and fro. Khan snatched it and, holding it close to the lantern, peered hard.

‘A necklace?’ asked Clara.

‘Pearls, I think,’ said Sophia.

Khan looked up. ‘You’d better be right, lady. It’s too dark to tell right now.’

‘Well, even if they’re fake,’ said Sophia, ‘they’ll be worth something.’

‘You took it from the farmhouse,’ said Clara. ‘You stole this, too . . .’

Khan chuckled. ‘I’ll let you off, both of you. Now come on. This way.’

–

Phil Gilvin lives with his wife in Swindon, nestling in the rolling downland of Wiltshire amid neolithic barrows, ancient droveways and stone circles – and the M4 motorway. When his children grew too old to have stories read to them he turned to writing, going to lots of workshops and winning a number of short story prizes. His short stories have regularly been shortlisted in magazine competitions and have featured in local anthologies. Truth Sister is his first published novel (his first two, unpublished, got consigned to the “that’s how you learn” pile). Phil’s other career is as a scientist (now part-time). He enjoys walking in aforesaid downland as well as listening to classical music and prog rock, and murdering folk songs.

Leave a Reply