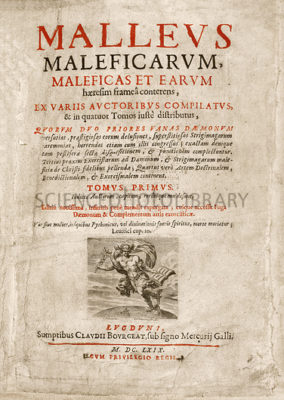

Malleus Maleficarum, Latin for ‘the Hammer of the Witches’, was a guide written in 1486 on how to identify, hunt and try witches. It was written by one of the most notorious witch hunters in history: Heinrich Kramer. This incredibly influential book attributed to the deaths of thousands – if not millions – of people, and has had a colossal impact on western culture.

Although believing in witches and witchcraft was deemed an act of heresy by the Catholic Church, Kramer, a German churchman and inquisitor, wrote Malleus Maleficarum as a way to disprove his critics. The book was endorsed by the Pope himself (although a ‘donation’ is said to have taken place) and is the only book on witchcraft to have ever received official approval of the church. Unsurprisingly, this approval gave enormous weight to Kramer’s words, and the book was incorporated into the judicial system of many European countries. Between the 16th and 17th century, 30,000 copies were in circulation throughout Europe and 60,000 people were put to death for witchcraft.

The modern-day translation of Malleus Maleficarum is actually quite palatable and an extremely fascinating read. It contains 256 ‘facts’ on the existence of witches and why it is necessary to kill them. These facts are presented in three parts.

The first part is entitled: ‘Treating on the three necessary concomitants of witchcraft which are the Devil, a witch, and the permission of Almighty God’. It contains a series of questions and solutions to witch-related arguments that were a point of discussion among the religious and judicial figures of the time. Some of the debates, including ‘whether children can be generated by Incubi and Succubi’, are particularly troubling. The solutions provided are just as harrowing: ‘For in the 18th chapter of Deuteronomy it is commanded that all wizards and charmers are to be destroyed.’

The reason that witches needed to be destroyed as opposed to helped or cured is outlined in part two: ‘it is unlawful to use the help of devils, since to do so involves apostasy from the Faith. And, it is argued, no witchcraft can be removed without the help of devils. For it is submitted that it must be cured either by human power, or by diabolic, or by Divine power.’ In other words, death is the only way to get rid of a witch.

Kramer also doesn’t hold back when delineating his immense distrust of women in the second part of the book. For instance, chapter seven is entitled, ‘How, as it were, they [witches] deprive man of his virile member’. There is a lot of information in this section that describes females bewitching men, possessing them and turning them into beasts. There is also an immense distrust for midwives as they can cause ‘most horrid crimes’. In reality it is the women that were hunted, harmed and persecuted unjustly.

In the third part of the book, Kramer discusses the judicial system and asks: ‘Who are the Fit and Proper Judges in the Trial of Witches?’ Of course, the answer is men such as himself: ‘If it is an ecclesiastical crime needing ecclesiastical punishment and fine, it shall be tried by a Bishop who stands in favour with God, and not even the most illustrious Judges of the Province shall have a hand in it’.

After the book was published, Kramer held his first successful trial against two women. He used the ‘strappado’ to get them to confess to witchcraft, which was his favourite torture device of choice. It involved pulling the wrists upwards until the victim was hanging by the arms, which forced the arms to dislocate. Once they had confessed, the two women were burned alive.

This is a hugely gruesome and unjust part of history, but witch hunts are still around today. In fact, the number of deaths from modern-day witch trials is thought to have far exceeded the number of those killed centuries ago. Most take place in sub-Saharan Africa, and many of the accused are children. Simply Google ‘modern witch hunts in Africa’ and you will be confronted with hundreds of alarming reports.

I initially wanted to read Malleus Maleficarum to blog about an interesting piece of historical horror, but it has led me down a path of research that was anything but entertaining. The persecution of women, children, the mentally and physically handicapped, foreigners and outsiders is still rife. It comes in different forms, but the issues are inherently the same. Are we better off than we were in 1486? Or do we just hide things in different ways?

Leave a Reply