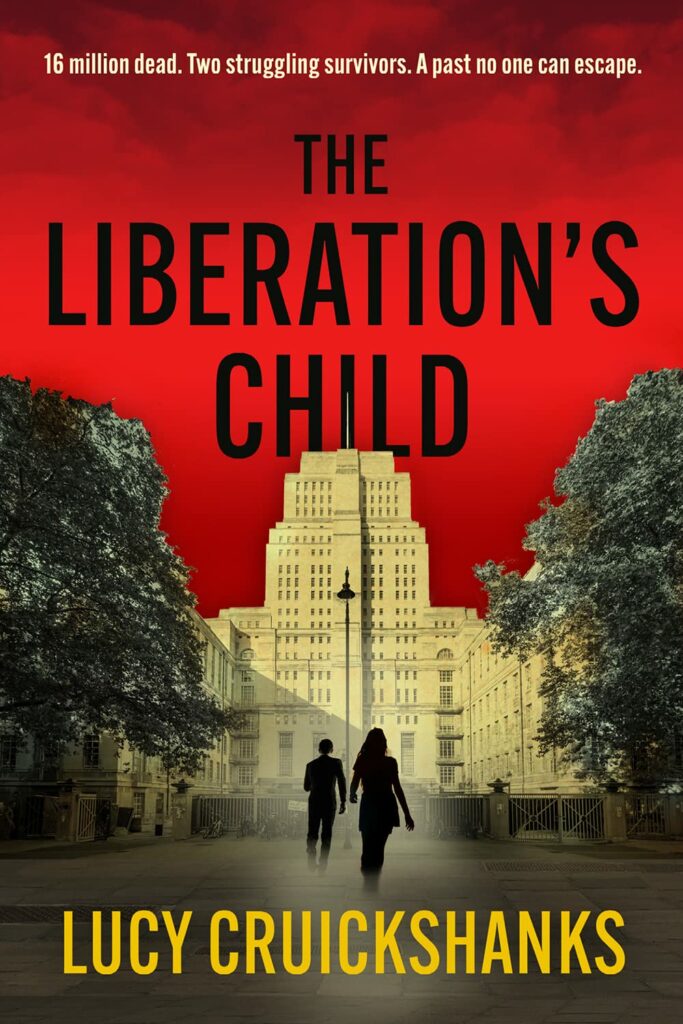

In the blurb for The Liberation’s Child, the novel has been described as set in ‘a Britain of the near future’. Near future? More like the now future. If you’re having difficulty facing the news at the moment, you might want to prep yourself for this harrowing read.

Set in London in the near future, the election of a political party named Free and Equal Britain, or FEB, is treated as a joyous victory for democracy. Cut to a few years later, and it turns out the FEB were just the Tories on steroids. Ever since, Britain has been attempting to recover from a devastating cocktail of corruption, genocide, violence and the complete destruction of the economy, and the idea of Britain being able to redeem its status as one of the most powerful countries in the world seems impossible.

The novel centres on the characters Thea and Dom, both survivors of the FEB era who were young when the party first got into power, but they have since lived very different lives. Dom was able to escape to America with his brother to start a new life, whereas Thea was trapped in London, always struggling to get by.

Thea is a single mother, but as she is unable to pay for the treatment she received after a difficult birth, the state has taken the child until she has earned enough credits (the new form of currency) to get her back. Yep, the glorious NHS is no more. One day, when Thea goes to visit her baby at the children’s home she is being kept at, the doors are locked. There are no sounds coming from inside. The windows are boarded shut. Thea tries to get the police involved, but they’re of no use. Where has her baby gone? And who will care enough to help her get her back?

Dom meanwhile has returned to London from America to adopt a child with his wife. They, like many couples across the globe, have been affected with fertility issues. He specifically wants to adopt from England to give a child the opportunities and freedoms he was given. But there’s something not right with the adoption process. He feels he is being lied to, particularly about how the babies have come to be in the care of the children’s home. After all, they are being adopted by rich foreigners willing to pay an extortionate price for them…

That’s when he and Thea cross paths. Together they begin to find out that, while the FEB movement has officially ended, their hold on the country has not.

A lot of this novel felt scarily close to home. The domination of a right-wing party, dangerous computer viruses, scandals, a degradation of democracy, even the reduction of fertility rates and adoption scandals felt eerily similar to those I’ve read about in recent history. The Britain depicted in The Liberation’s Child is battered, bruised, furious and grieving all at once.

The story was incredibly fast-paced, with a detective element that I truly love in dystopian fiction. The characters were nuanced and sympathetic, and I felt every blow they were dealt. Cruickshanks’ writing is also captivating, teasing out the information that made this a true page-turner, if you would forgive the cliché.

My only issue with The Liberation’s Child is that this image of Britain was too ravaged for me, the characters too broken. It was unrelentingly. I often felt it lacked breathing space. It sometimes seemed more of a hellscape than a possible future reality. And yet, it resembled so much that’s happening right now that perhaps I’m simply unable to stomach dystopian novels reflective of current events. Am I just too sensitive to Britain’s possible demise?

I think this might be the case. The Liberation’s Child is a riveting novel, and I recommend diving straight into it if your stomach is stronger than mine. If not, perhaps wait until after the next election to see if there is a glimmer of hope for us.

Leave a Reply